On Friday, May 21, I took a break from work and from the Texas Hill Country and went wandering south of Austin to explore the birdlife in the area around Seguin and Guadalupe County. I should mention--and this will come as something of a shock to some of you--that I don't often go birdwatching during my time off. I watch birds...and everything else in the natural world...in my free time, but I had mostly gotten out of the habit of chasing birds.

But this Spring has been an exception to my sedentary ways of recent years. I have been inspired by the "Texas Century Club" effort of the Texas Ornithological Society to see at least 100 species of birds in each Texas county. I'm not aiming at all 254 Texas counties, but I thought I'd see if I could meet that mark in each of the 15 counties which make up the bulk of the "Austin Area Checklist Circle"--the area within a 60-mile radius of the Texas Capitol building. Perambulation in moderation, so to speak. But that's still a huge area to explore--about 11,309 square miles if you do the math.

For Guadalupe County, I could find mention of only 53 species of birds I had seen in past excursions. I had passed through the county en route to other destinations innumerable times, especially along Texas 123 racing towards the Texas Coastal Bend and its abundant birdlife. But Seguin and environs had rarely enticed me to stop and explore. So that Friday, I was going to make amends for past transgressions--literally--and see what avian offerings the area had.

I had done my homework: I studied county road maps and Google Earth, chatted with local birders, and scoured previous postings on TexBirds to see what might await. I had a plan... Maybe that was the problem: I had a "plan". [Insert your favorite cliché here.]

Max Starke Park in Seguin, one of my birding destinations.

I got a very early start, arriving in the eastern corner of the county pre-dawn, early enough to hear a Common Nighthawk in its last foraging bout over an open pasture and to flush a Chuck-will's-widow off a paved county road--the last pavement I would see for several hours. Along FM 1150, then onto Nixon Road, then off the pavement onto Dix Road and then to Nash Creek Road which is a major connecting route to, ... well, to the other end of FM 1150. I stopped several times to listen to the dawn chorus. By 6:30 a.m., even before the sun came up, I had tallied 20 species or so. Northern Cardinal, Bewick's Wren, Mourning Dove, Painted Bunting, Ash-throated Flycatcher ... Wait a minute!  That's not an Ash-throat singing, it's a Brown-crested Flycatcher, its South Texas cousin and one of the rarest breeding birds on this southern fringe of the Austin checklist circle. Woo-hoo! That got a big asterisk in my field journal.

That's not an Ash-throat singing, it's a Brown-crested Flycatcher, its South Texas cousin and one of the rarest breeding birds on this southern fringe of the Austin checklist circle. Woo-hoo! That got a big asterisk in my field journal.

Then somewhere between that Brown-crested Flycatcher and an anonymous farm gate about 2 miles down the road, I lost that field journal. I apparently made a note about another dawn singer, set the journal on the hood or bumper of my truck, got distracted by another bird or some darned wild thing on the roadside, and then jumped in the truck and drove away. Since I was scribbling notes in the journal at almost every listening stop, it was only a few minutes later that I realized I was missing the journal. I backtracked on the road and couldn't find it.  I spent the next 3 hours walking that two-mile stretch of road and never found it. A yellow-green journal in a sea of yellow-green foliage. I was envisioning a cow in an adjacent pasture stomping my journal deep into the mud, or a county mower shredding it like so much other mulch on the roadside.

I spent the next 3 hours walking that two-mile stretch of road and never found it. A yellow-green journal in a sea of yellow-green foliage. I was envisioning a cow in an adjacent pasture stomping my journal deep into the mud, or a county mower shredding it like so much other mulch on the roadside.

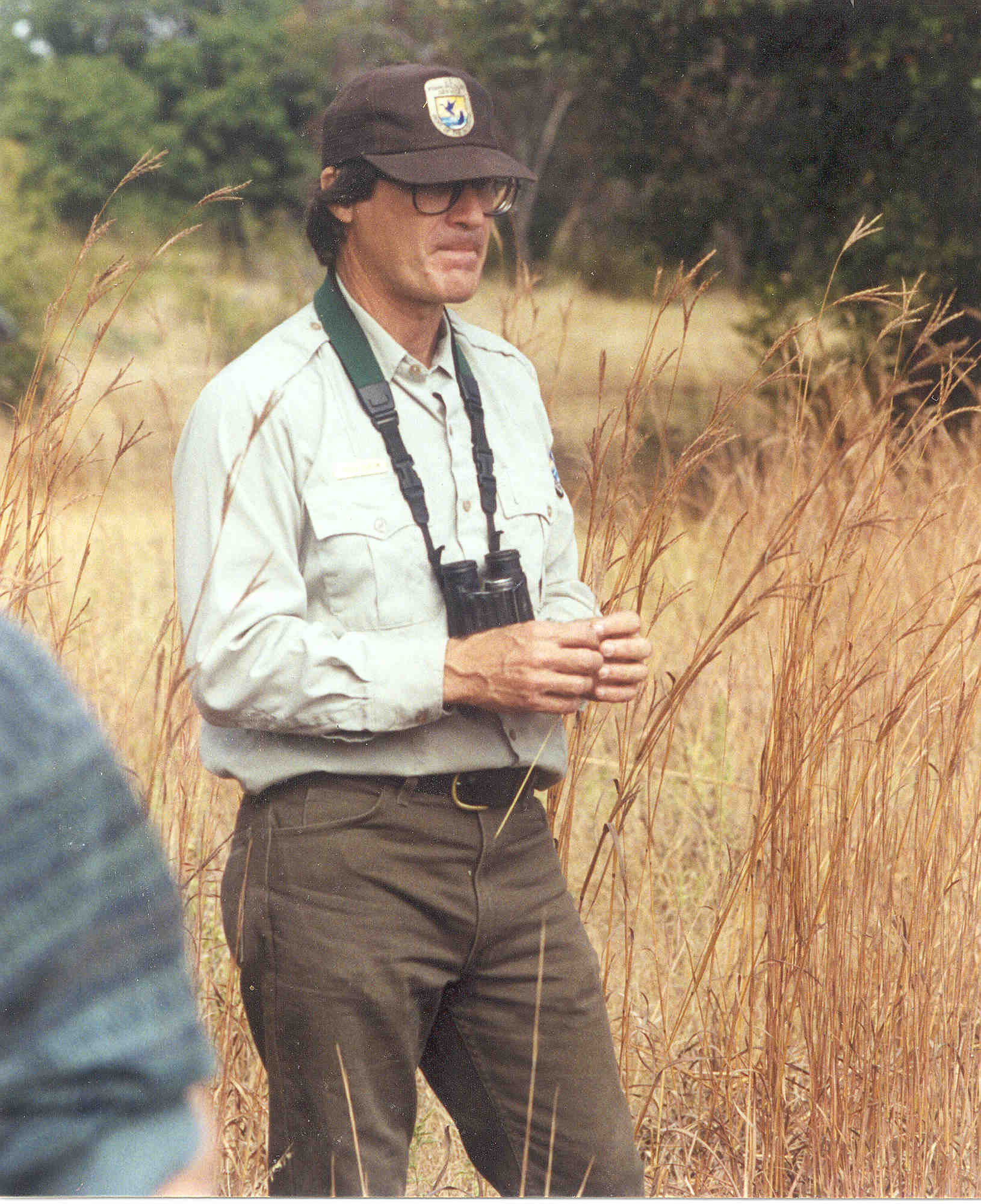

Well, to make a long story just somewhat shorter, a passerby--a local resident on Nash Creek Road--retrieved my journal and mailed it back to me just a few days later. It was probably just a bit of odd timing; he'd found the journal in the middle of the road but hadn't realized that the journal's owner was that out-of-place stranger a short ways down the road, raising his binoculars and staring off into the distance. No harm, no foul. Just great consternation on my part for several days.

I mention all this just to get around to the topic at hand: What would have been lost had that journal never turned up? It was the latest of 63 volumes of my field notes, but it was less than half filled with my scribbles. I had just started the volume on April 1 and had already photocopied all the Refuge field notes for April. I hadn't copied my own personal birdwatching notes for other April days, nor had any of May's notes been duplicated. Would that Brown-crested Flycatcher on Nash Creek Road have disappeared into anonymity? Of course not. It is more a measure of my unhealthy reliance on my journal-crutch. Precisely 27 pages of my life's work, spanning just over 21 days, would have been lost. And for that, I wasted three perfectly good hours on an early morning birding jaunt, and several days of mourning.

For the record, here are some of the earth-shaking, history-making data for May that might never have seen the light of day, some of which were fortunately documented by photographs:

-- May 2: I jotted down a second-hand report from David Maple that he'd seen a male Lark Bunting in breeding plumage  near the Barho tract, a rare spring sighting.

near the Barho tract, a rare spring sighting.

-- May 3: I briefly resighted a Lazuli Bunting that Rob Iski had found on April 29 on the Post Oak Creek Trail; first I'd ever seen on the Refuge.

-- May 3: A male Bell's Vireo was singing on territory near the photo blind, the fifth species of breeding vireo on the Refuge this year (along with Black-capped, White-eyed, Red-eyed, and Yellow-throated).

-- May 7: I found a new karst feature, a hole in the ground, on the Rodgers tract and named it the "Grape Joint". At Doeskin Ranch in the afternoon, I discovered that I had missed the blooming of our Shooting Star flowers along the Rimrock Trail; make a note to look for them in mid-April.

-- May 7: I found a new karst feature, a hole in the ground, on the Rodgers tract and named it the "Grape Joint". At Doeskin Ranch in the afternoon, I discovered that I had missed the blooming of our Shooting Star flowers along the Rimrock Trail; make a note to look for them in mid-April.

-- May 9: SCA Student Elizabeth Lesley found her dog playing with a dog-slobber-covered Coral Snake in her yard.

-- May 10: On the Martin tract, an Eastern Hognose Snake feigned death for me like only a hognose snake can.

-- May 14: Visited a large private ranch in n.w. Burnet County where conservation banking is being proposed. On the distinctive Paleozoic limestones in that region, it's difficult to figure out the dynamics of the warbler and vireo habitat, but our colleagues in the regulatory side of FWS want some answers.

-- May 16: Helped with a breeding bird survey on the Bamberger Ranch and spent the rest of the day birding in Blanco County to pad my county list there. Best bird of the day: Cactus Wren near the community of Sandy.

-- May 17: Lots of painted lichen moths and  bird-dropping mimic moths at the porch light at the office in the morning.

bird-dropping mimic moths at the porch light at the office in the morning.

Three or four (or five or six?) moth species,

all with the same survival strategy.

-- May 20: Photographed a huge female Dobsonfly at our office door.

-- May 20: Photographed a huge female Dobsonfly at our office door.

-- May 21: Guadalupe County birding trip: ***Brown-crested Flycatcher (2+ singing in dawn chorus)...

* * * * *

Below The Line:

Oh, How did my "Century Club" effort on the quiet roads of Guadalupe County turn out? I almost met my goal: By the end of the day, I had added 40 new species to my county list, ending the (frustrating) day at 93 species. I missed Blue Jay, Orchard Oriole, and Indigo Bunting, leaving something for a future visit.

Notes from the Canyonlands

Notes from the Canyonlands