What could be more enjoyable on a cold winter morning than kicking through a grassland recently “decorated” by grazing cattle, or picking your way through prickly-pear when you really want to concentrate on that itty-bitty little brown job that just dove into the bush up ahead, or daintily dancing over a chilly prairie creek to chase a bird that doesn’t know the real meaning of ‘swamp’? It don’t get any better than this!

Bill Reiner Jr., Byron Stone, and I each came to appreciate sparrows from slightly different birding pathways but in the end, we all became Emberizid Enthusiasts, Ambassadors of Aimophila, Spizella Specialists, Purveyors of Pipilo, or whatever epithet you might dream up. Personally, I've always liked a bird ID challenge. If I lived near the coast, I’d spend more time with confusing immature gulls. If I lived in the eastern woodlands, I’d strive to pick up the identification subtleties of migrant warblers in dull fall plumage. But having started my birding career in the dead of winter in the mesquite plains around San Angelo, Texas, if I couldn’t get enthusiastic about studying sparrows, I wouldn’t have had much to look at. Texas in general, and the eastern edge of the Texas Hill Country in particular, offers a high diversity of these dashing little feathered dinosaurs for our viewing pleasure. They may not be as gaudy as spring warblers, buntings, or orioles, but they are jazzy in the own subtle ways of plumage and behavior.

"Sparrows? I don't know nothin' about no sparrows.

"Sparrows? I don't know nothin' about no sparrows.

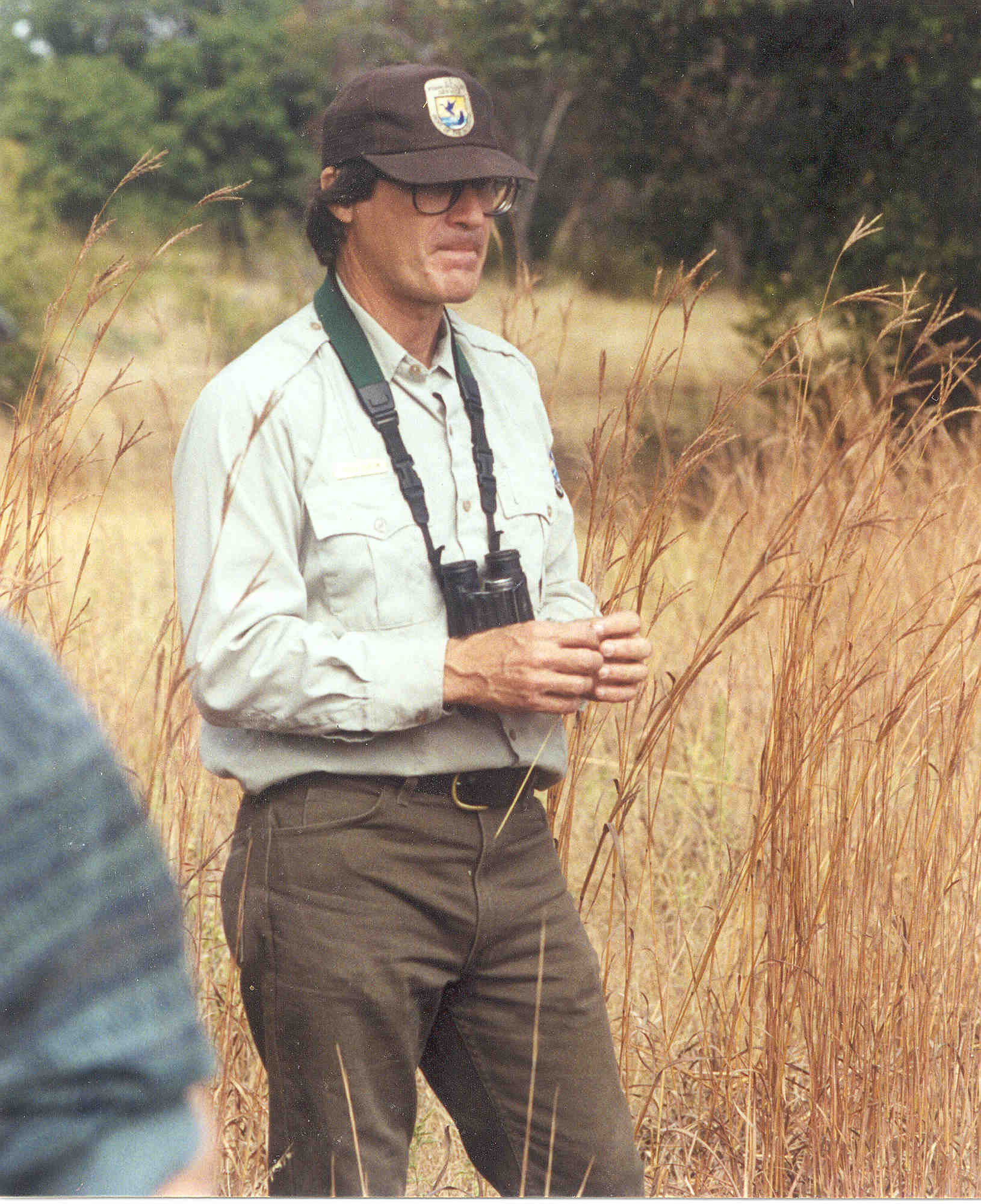

I thought I was supposed to lead a winter *bud* identification field course."Photo: Charles Mickel This year’s participants were treated to a beautiful weather day. A nice chill in the morning was sufferable. The afternoon was so nice that even the sparrows took some time off, much to our chagrin. (I thought they were contractually obligated to stay easily visible, but apparently they hadn’t read the fine print.) Nonetheless, a grand time was had by all, with the intensity and enthusiasm of the morning gradually morphing into an easy camaraderie and chatter about a day well-spent.

Statistically, the day was hit and miss. (See a complete bird list "

Below The Line".) We tallied a total of 17 species of “sparrows”, in the familial sense of the word. We missed five of our “regulars” (Black-throated, White-throated, and Swamp Sparrows, Eastern Towhee, and, of all things, Dark-eyed Junco), but made up a little ground with a Lark Bunting glimpsed and photographed by Byron, and .... drum roll, please .... a new species for the Refuge:

Brewer’s Sparrow. The latter was identified by Bill Reiner and his group on their morning tromp around the Flying X. [Historic note: Bill had added the elusive Baird’s Sparrow to the Refuge list with a sighting barely a hundred yards away from the same spot on April 22, 2006. He has the knack, and the Flying X provides the show.]

My two tours couldn’t match the diversity of Byron’s or Bill’s but what we lacked from the list, we made up for in quality looks at some specialties like Rufous-crowned Sparrow and Canyon Towhee. In fact, a pair of Canyon Towhees at Hickory Pass Ranch provided book-ends to our day, popping up to make them the first birds studied in the morning sun and bidding my group fairwell as the sun dropped behind the trees in the late afternoon. SparrowFest 2010 has come and gone and we all survived. Below, I forward some of the documentation, kindly provided by Laurie Foss, Fred Zagst, and Charles Mickel.

I offered my morning group the option of visiting two distinctly different habitats:

Climbing up the vertical cliff adjacent to Cow Creek,

or walking through the flat grassland...

Happily, they chose the latter.Photos: Laurie Foss

Happily, they chose the latter.Photos: Laurie Foss The early bird(ers) got the (Brewer's Sparrow) worm ...

The early bird(ers) got the (Brewer's Sparrow) worm ...

(Well, I guess that proverb doesn't transpose smoothly for present purposes.)

Here, the midday crowd attempts to refind that 1st Refuge record at the Flying X.Photo: Charles Mickel Turnabout is fair play:

Turnabout is fair play:

Bill Reiner's afternoon group searches in vain for a Black-throated Sparrow.Photo: Charles Mickel One of the cooperative Canyon Towhees at Hickory Pass Ranch,

One of the cooperative Canyon Towhees at Hickory Pass Ranch,

warming up--like the rest of us--in the morning sun.

Photo: Fred Zagst

* * * * *

Below the Line:

A small sampling of sparrows in literature (other than field guides):

“I once had a sparrow alight upon my shoulder for a moment while I was hoeing in a village garden, and I felt that I was more distinguished by that circumstance than I should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.”

Henry David Thoreau, Winter Visitors

“Whenever I hear the sparrow chirping, watch the woodpecker chirp, catch a chirping trout, or listen to the sad howl of the chirp rat, I think: Oh boy! I'm going insane again.”

Jack Handey, Deep Thoughts

* * * * *

Further Below The Line -- SparrowFest 2010 Bird List:

Northern Bobwhite

Black Vulture

Turkey Vulture

Northern Harrier

Cooper's Hawk

Red-tailed Hawk

Crested Caracara

American Kestrel

Merlin

Wilson's Snipe

Eurasian Collared-Dove

Mourning Dove

Great Horned Owl

Red-bellied Woodpecker

Centurus sp. (prob. Golden-fronted Wdp.)

Ladder-backed Woodpecker

Northern Flicker

Eastern Phoebe

Western Scrub-Jay

American Crow

Common Raven

Carolina Chickadee

Black-crested Titmouse

Carolina Wren

Bewick's Wren

House Wren

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Eastern Bluebird

Hermit Thrush

American Robin

Northern Mockingbird

Brown Thrasher

European Starling

American Pipit

Cedar Waxwing

Orange-crowned Warbler

Yellow-rumped Warbler

Spotted Towhee -- a few here and there; fewer than normal

Canyon Towhee -- two pairs at two locations

Rufous-crowned Sparrow -- small numbers, great looks

Chipping Sparrow -- common in edges and woodlands

BREWER'S SPARROW -- one at Flying X, 1st for Refuge

Field Sparrow -- common and widespread

Vesper Sparrow -- fairly common, widespread

Lark Sparrow -- at least 10 at Peaceful Springs

Lark Bunting -- one photographed on Eckhardt (ByS)

Savannah Sparrow -- abundant in grasslands, etc.

Grasshopper Sparrow -- fairly numerous in grasslands, etc.

Le Conte's Sparrow -- numbers seen well by 4 of 6 field trips

Fox Sparrow -- a few, scattered

Song Sparrow -- fairly common

Lincoln's Sparrow -- fewer than normal, but fairly common

Harris's Sparrow -- small numbers at two locations

White-crowned Sparrow -- fairly numerous

Northern Cardinal

Eastern Meadowlark

Western Meadowlark

Brewer's Blackbird

Brown-headed Cowbird

House Finch

Lesser Goldfinch

American Goldfinch

House Sparrow

Notes from the Canyonlands

Notes from the Canyonlands