A few weeks ago, a small team consisting of myself, David Maple, Elizabeth Lesley, and Jean Nance hiked to those big junipers I had reported earlier in the Post Oak Creek watershed ("The Wonderland of Post Oak Creek", Feb. 10) to get some good measurements on the trees. I report the results below, but first I thought it might be instructive to describe how big trees are measured. The answer: "...with difficulty."

There are a number of technical points on what constitutes a standard--or official--measurement of a tree. The best starting point for learning about this is on the Texas Forest Service's website for the

Texas Big Tree Registry. At that site you can learn "

How to measure a big tree" and the details of the "

Measuring rules". You can also view or download the "

Registry of Champion Trees" and a nomination form, if desired. Lifted directly from their information, here is an overview of how to measure a big tree:

The starting point is the "

DBH point" which refers to the "diameter at breast height" and is defined as 4.5 ft above the ground level. Rather than using the diameter of a tree, the size is actually gauged on the

circumference of the trunk. This is "

the smallest circumference between the DBH point (4.5 feet) and the ground, but below the lowest fork." As you can imagine, there are complications for multi-trunked trees, leaning trees, trees on slopes, etc. The TFS website explains what to do in those circumstances. For big tree measurements, the TFS uses English units of measure; the circumference is reported in inches.

The

height of a tree, of course, is an integral part of the calculation but this can be the trickiest part to measure, especially in a heavily wooded setting. I discovered that my "ocular estimates" reported previously ("50+ feet") were too generous. If you believe all the botany texts, properly measuring the height of a tree would seem to require an advanced degree in mathematics with an emphasis on trigonometry.

Luckily, there are any number of modern forestry tools to accomplish the task of sizing up a tree. Unfortunately, we had none of those at hand, so we used a modified version of the "stick method". (Lest your imagination run amok, yes, we did the subsequent calculations on an abacus and dutifully recorded the data on a clay tablet...) By this, you have some standard reference height positioned at the tree (a person of known height, or a pole of known length). Then, you back off a substantial distance and use some calibrated "stick" (in our case, a standard 12-inch ruler) to gage the relative height of the tree versus your measurement standard. Got that? For instance, while Elizabeth Lesley held up a 3-meter pole at the trunk of one big juniper, I stepped back until I could match the 3-meter pole with the 3-inch mark on my ruler. The top of the tree happened (by coincidence) to match the length of the ruler exactly--12 inches--so some easy math allowed me to determine that the tree was 12 meters tall. Converted to English units, that is 39.4 ft, which by the TFS rules is reported as 39 ft tall.

The last measurement of a tree which goes into the formula for its score is

Average Crown Spread. To measure this, you figure out the "drip line" of the tree, which can be visualized as the shadow of the tree's crown projected vertically onto the ground. You then measure its widest dimension. The second measure is the widest width at any point

perpendicular to that longest diameter. The two perpendicular widths don't have to intersect at the trunk of the tree; sometimes they will, sometimes not. The Average Crown Spread is the average of the two widths.

For purposes of comparing trees and deciding a champion, the TFS calculates a "

Tree Index" by adding together the circumference (inches), the height (feet), and one quarter of the average crown spread (feet), rounded to the nearest whole number.

Tree Index = circumference (in) + height (ft) + 1/4 of avg. crown spread (ft)

So how did our big junipers stack up? We measured two of the five big trees in the grove. The tree pictured in my previous blog measured 72 inches in circumference (just shy of 2 ft in diameter), 39 ft tall, and had an average crown spread of 42 ft, giving it a tree index of 72 + 39 + 42/4 =

122. A second large juniper measured: circumference, 65 inches; height, 41 ft; average crown spread of 38 ft, giving an index of

116.

The champion Ashe juniper is a bulky monster in New Braunfels which is not much higher (41 ft) nor wider (49 ft) than our trees, but it has a thick truck measuring 139 inches around, giving it an index of

192.

The State and National Champion Ashe Juniper

The State and National Champion Ashe Juniper

New Braunfels, Texas[photo credit unknown; downloaded from the Junipers of the World website]

You can find information about champion trees all over

the country at

American Forestry's National

Register of Big Trees. Can any of these big juniper trees be aged? Typically, foresters would estimate the age of a living tree by drilling a very narrow core to the center of the tree (the width of a soda straw), taking that core back to the lab and counting the growth rings under a microscope. For junipers, this traditional method of counting tree rings is very

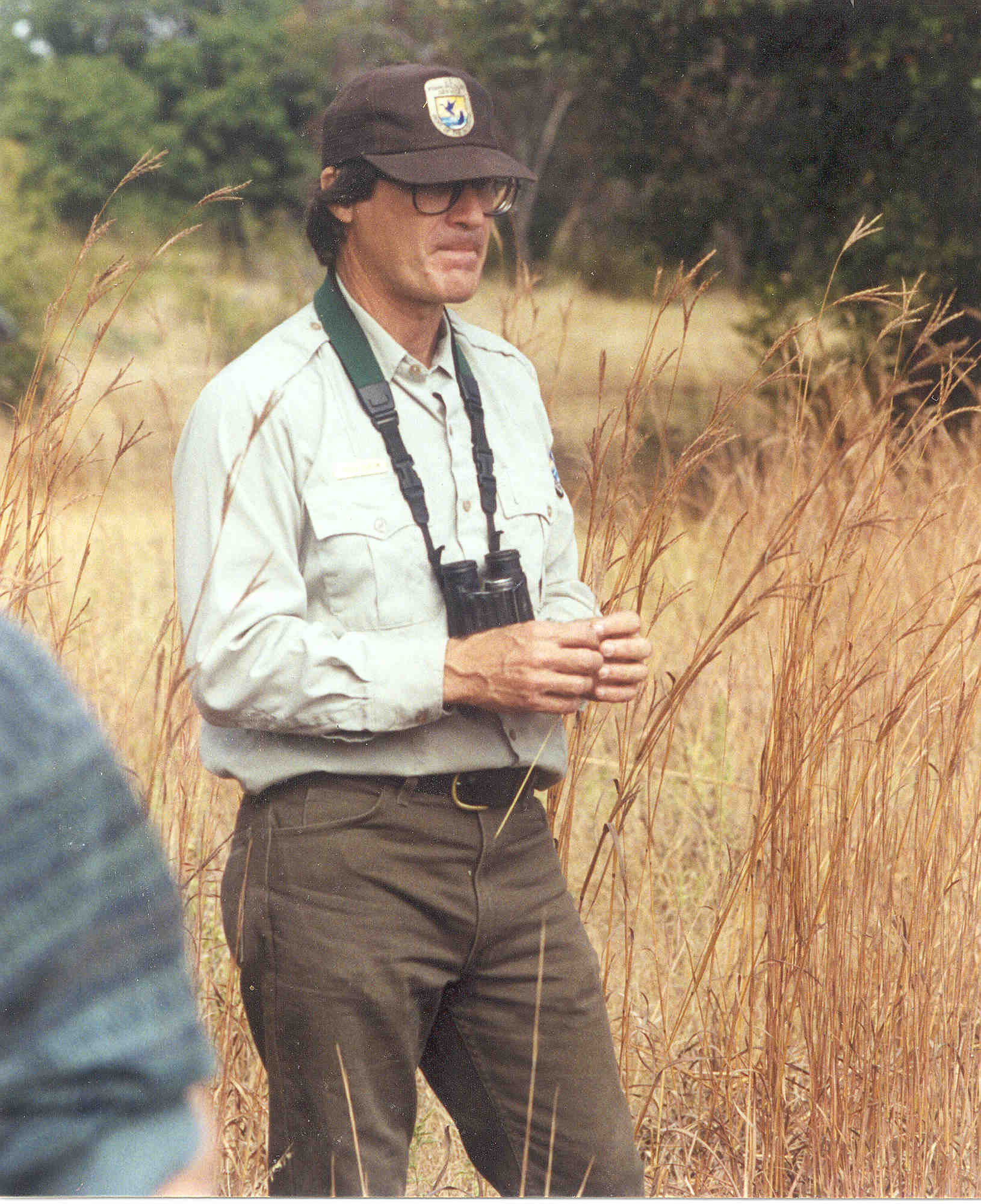

unreliable. I saw a vivid illustration of this last week when I was examining some other habitat management we are doing. On the Refuge's Webster tract, we recently put in a deer-proof fence to enclose a rather large area of Golden-cheeked Warbler habitat in a study being conducted in collaboration with the University of Texas. A number of various sized junipers had to be felled to put the fence in. That gave me the opportunity to examine the growth rings on some freshly cut juniper trunks. Take a look at what I found:

Look closely at the (dark) rings on this juniper; a lot of them look "double". Many of these probably represent separate growth spurts by the tree in the spring (wider rings) and after late summer or fall rains (narrow rings). Sometimes these might represent growth in a wet year followed by a dry year. There is no easy way to tell the difference in these two scenarios. The conclusion: Ashe junipers don't have a simple correlation of growth rings to annual cycles.

The second major problem with aging such trees is that junipers don't always put on new growth in neat rings evenly distributed

around the trunk. Look carefully at the pattern here, where growth seems to occur irregularly at different places on the tree at different times (years), resulting in a pattern that looks like silt fans at a river delta or wind-blown sand dunes. This is an intriguing growth strategy and I don't know why it happens. Once again, imagine trying to core through any one location in this juniper; it would only be by accident that you might pierce through a complete and countable set of growth rings.

* * * * *

Below the Line:

The fact that my original estimates of the height of those big junipers were so far off ("50 ft" versus the reality of ~40 ft) shook my confidence to the core. Over my years in the field I've had much time to hone my estimation skills--based on comparisons to objectively measured heights, lengths, distances, sizes, etc.--and it is something I have had a quiet confidence in. Or not-so-quiet if you've ever been on a deer count on a Fall evening with me and I boldly announce the temperature after waving my hand in the air for a few seconds. My hand is rather well-calibrated to air temps (in degrees Fahrenheit). My estimates of any given measure might be blurted out in English or metric units; it's not that I convert those easily in my head but it comes from whatever I worked with for standard measurement in a given discipline (e.g. measuring the sizes of plant parts in mm and cm versus estimating the size of a bird in inches or the distance of a hike in miles).

Notes from the Canyonlands

Notes from the Canyonlands